Puppy and Dog Vaccinations: A Schedule for Every Life Stage

Adobe Stock/Ievgen Skrypko

Dog vaccinations are critical to ensuring your four-legged friend stays healthy from puppyhood into their senior years. Vaccines are the safest and most cost-effective way to protect your dog from many infectious preventable diseases.

The science behind canine vaccinations has progressed significantly over the past decade, enhancing both their safety and efficacy against existing and emerging pathogens. Here’s why vaccinating a dog is important.

For PetMD's complete guide on dog vaccinations and when your pet should get them, click here.

For the Spanish version, click here.

What Are the Common Dog Vaccinations?

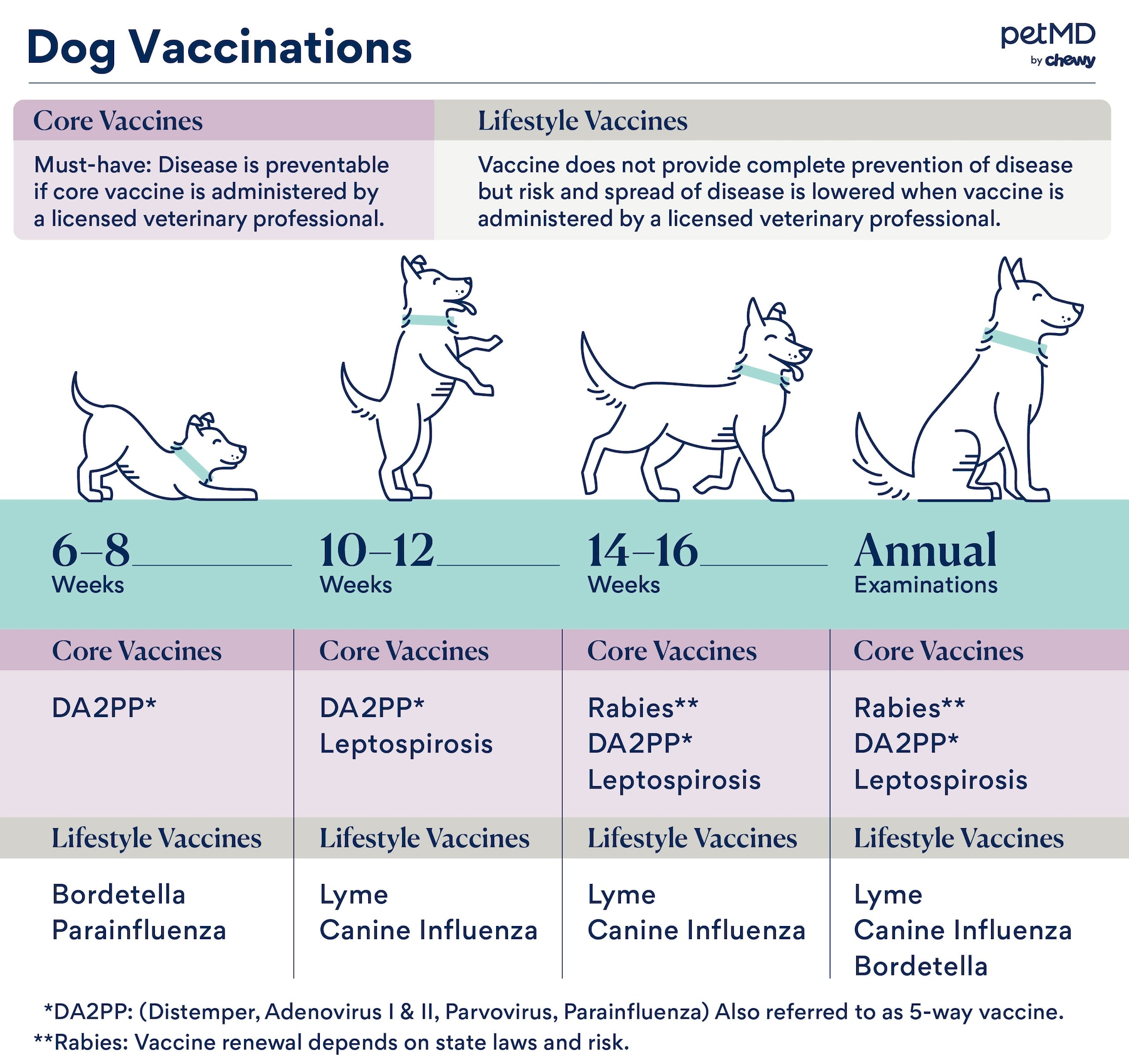

Dog vaccinations are split into two general categories: core vaccines and lifestyle vaccines.

Core Vaccines

Core vaccines are required for all dogs and puppies. Core dog vaccines include:

-

Canine distemper/adenovirus-2 (hepatitis)/parvovirus/parainfluenza vaccine (given as one vaccine and commonly referred to as DA2PP, DHPP, or DAPP)

-

Leptospira (Leptospirosis) vaccine (this can also be given in combination with the DA2PP/DAPP vaccine, as the DHLPP vaccine)

Lifestyle Vaccines

Lifestyle vaccines are considered optional and given based on factors such as your pet’s lifestyle and where you live. Several lifestyle vaccines protect against highly contagious or potentially life-threatening diseases.

To determine which lifestyle vaccines are appropriate for your dog, your vet will look at a variety of factors, including:

-

Geographic location and risk of disease in these areas

-

Whether your pet goes to doggy day care, dog parks, or boarding or grooming facilities

-

Your pet’s lifestyle, including traveling, going on hikes, or being exposed to the wilderness

-

The overall health of your pet

Lifestyle vaccines include:

-

Bordetella bronchiseptica (kennel cough) vaccine

-

Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme) vaccine

-

H3N2/H3N8 (canine influenza) vaccines

-

Crotalux atrox (rattlesnake) vaccine

Puppy Vaccine Schedule

So, when do puppies need shots?

For puppy vaccines to provide necessary protection, they’re given every two to four weeks until a puppy is at least 16 weeks old. Certain breeds and puppies in high-risk areas may benefit from receiving the last vaccines at around 18–20 weeks old.

Here’s an example of what a typical puppy shot schedule looks like:

| Age | Core Vaccines | Lifestyle Vaccines |

|---|---|---|

| 6–8 weeks | DAP* | Bordetella Parainfluenza (often included in DA2PP combo vaccine) |

| 10–12 weeks | DHLPP | Lyme Canine influenza |

| 14–16 weeks | DHLPP (vets prefer giving final DHLPP vaccine at 16 weeks or later) Rabies vaccine (may be given earlier if required by law) | Lyme Canine influenza |

*DAP (Distemper, Adenovirus/Hepatitis, Parvovirus. Sometimes also referred to as DHP or DHPP if parainfluenza is included, or DHLPP when Leptospirosis is included.)

Ultimately, it’s important to consult with your veterinarian to identify the appropriate schedule for puppy vaccines for your specific pet.

If you want to socialize your puppy safely while waiting for their vaccine schedule to be completed, consider using a dog stroller or a dog backpack carrier to keep your puppy off the ground.

Adult Dog Vaccine Schedule

Adult dogs need their core vaccines in addition to any lifestyle vaccines decided upon between you and your veterinarian. A dog vaccination schedule for an adult dog may look like this:

| Frequency | Core Vaccines | Lifestyle Vaccines |

|---|---|---|

| Annual vaccines for dogs | Rabies (initial vaccine) Leptospirosis | Lyme Canine influenza Bordetella (sometimes given every six months) |

| Dog vaccinations given every three years | DAP Rabies (after initial vaccine, given every three years) | No three-year lifestyle vaccines are available at this time |

Ultimately, your veterinarian will determine how long a vaccine will work for your pet.

If your dog is overdue or if it’s their first time getting a vaccine, your vet may recommend a booster vaccine or an annual schedule so your pet is fully protected.

What Diseases Do Dog Vaccines Prevent?

Keeping up with your dog vaccinations is the best way to protect your pup from many different illnesses, including:

Rabies

Rabies is a virus that causes neurologic disease that is fatal for domestic pets, wildlife, and people. It’s most notably transmitted through a bite from an infected animal. If your dog has rabies, it can be transmitted to you or other people through bite wounds.

The rabies vaccine for dogs is required by law in the U.S. Despite the excellent vaccination system in place, there are still cases of rabies reported each year.

Due to the fatality and zoonosis (meaning it can be transmitted from animals to people) associated with rabies, there are legal ramifications if your pet is not current on their rabies vaccine. Therefore, it’s extremely important to keep your pet up to date.

It’s important to consult with your veterinarian to identify the appropriate schedule for puppy vaccines for your specific pet.

If an unvaccinated dog or a pet that’s past due for their rabies vaccine is exposed to a potentially rabid animal or accidentally bites someone, it may result in health concerns, the need to quarantine your pet, or humane euthanasia in certain circumstances.

Distemper/Adenovirus (Hepatitis)/Parvovirus (DAP)

The DAP vaccine protects against a combination of diseases that can spread quickly among dogs and have serious implications for canines, including severe illness and death.

-

Canine distemper is a devastating disease that is highly contagious in unvaccinated dogs. It can result in severe neurologic signs, pneumonia, fever, encephalitis, and death.

-

Adenovirus 1 is an infectious viral disease also known as infectious canine hepatitis. It causes upper respiratory tract infections as well as fever, liver failure, kidney failure, and ocular disease.

-

Parvovirus in dogs is particularly contagious and can cause severe vomiting, diarrhea, lethargy, dehydration, and death in severe cases.

Oftentimes, the lifestyle parainfluenza virus is also combined in this vaccine, changing the vaccine’s name to DAPP or DHPP.

Bordetella and Canine Parainfluenza

Bordetella and canine parainfluenza virus are two agents associated with a highly contagious cough commonly known as kennel cough, or canine infectious respiratory disease complex (CIRDC).

Diseases from these agents typically resolve on their own, but they sometimes lead to pneumonia or more severe respiratory disease. Because kennel cough is so contagious, boarding and doggy day care facilities across the U.S. require your pet to have this vaccine.

Parainfluenza may or may not be included in a combination vaccine with Bordetella or the DAP.

Canine Influenza

Canine influenza in the U.S. is caused by two identified strains of the virus: H3N2 and H3N8. It is highly contagious and causes a cough, nasal discharge, and low-grade fever in dogs.

Outbreaks in the U.S. draw a lot of attention, as influenza viruses can give rise to new flu strains that have the potential to affect other species and possibly cause death.

Typically, the canine influenza vaccines are recommended for dogs that go to day care, boarding facilities, the groomer, or any place where they will be among other dogs. Talk to your vet about whether this dog vaccine is recommended for your pet.

Leptospirosis Disease

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease that can cause severe kidney or liver failure in dogs and people. It’s transmitted via the urine of infected animals and is found in both rural and urban settings.

Formerly considered a lifestyle vaccine, the leptospirosis vaccine is now a core dog vaccine. Dogs can be exposed to this illness by licking or coming in contact with a contaminated puddle or body of water where an infected animal has urinated.

Traditionally, the leptospirosis vaccine was only recommended for dogs in rural areas with outdoorsy lifestyles. But leptospirosis has now been found to occur in suburban and urban settings, too. The city of Boston experienced an outbreak in 2018 likely due to the urine of infected city rats.

Leptospirosis can be transmitted to people as well. Talk to your vet about whether they recommend this vaccine for your pet. The vaccine covers four of the most common serovars of leptospirosis, and the initial vaccine must be boostered two to four weeks later, and then annually thereafter.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is a tick-borne disease caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria that can cause fever, lethargy, decreased appetite, shifting leg lameness, and kidney failure in severe cases.

Lyme disease is endemic in various areas around the country (such as the Northeast, northern Midwest, and Pacific coast), and the vaccine is recommended in these areas and for dogs traveling to places with high rates of the disease. Talk to your vet if this vaccine is recommended for your dog.

Like leptospirosis, the vaccine is initially given as two injections spaced three to four weeks apart, and then yearly after that.

Which Dog Vaccines Does My Pet Need?

It’s important to discuss your dog’s lifestyle with your veterinarian so they can make appropriate recommendations regarding vaccines for your dog.

How Much Do Dog and Puppy Vaccines Cost?

Puppy and dog vaccine costs may vary depending on where you live. Typically, the basic DHLPP vaccine can cost $20–$60 per shot, while the rabies vaccine may be $20–$30. Other non-core vaccine prices can vary but are generally less than $100 per shot.

Vaccines are an essential part of dog and puppy care, and it is important to budget appropriately for them—especially when getting a new puppy. Puppies typically receive several different vaccines, often with boosters. But once they have been fully vaccinated, puppies transition to an adult vaccine schedule of annual (or even every three years) vaccines.

So, while getting a puppy started on vaccines may be an investment, this financial obligation will decrease during adulthood.

To help offset the cost of vaccines, many local animal shelters or humane societies have low-cost or even free vaccine clinics. Your veterinarian may be able to help identify these local options.

Additionally, pet insurance may be a good way to help offset these costs. Many insurance carriers will have wellness or preventative care plans to cover some (or all!) of the core and non-core vaccines.

While getting a puppy started on vaccines may be an investment, this financial obligation will decrease during adulthood.

Can Pets Have Adverse Reactions to Vaccines?

Dogs can have adverse reactions to canine vaccinations, medications, and even natural vitamins and supplements. These incidents are rare, but because they do occur, it’s important to monitor your pet after their vaccine appointment.

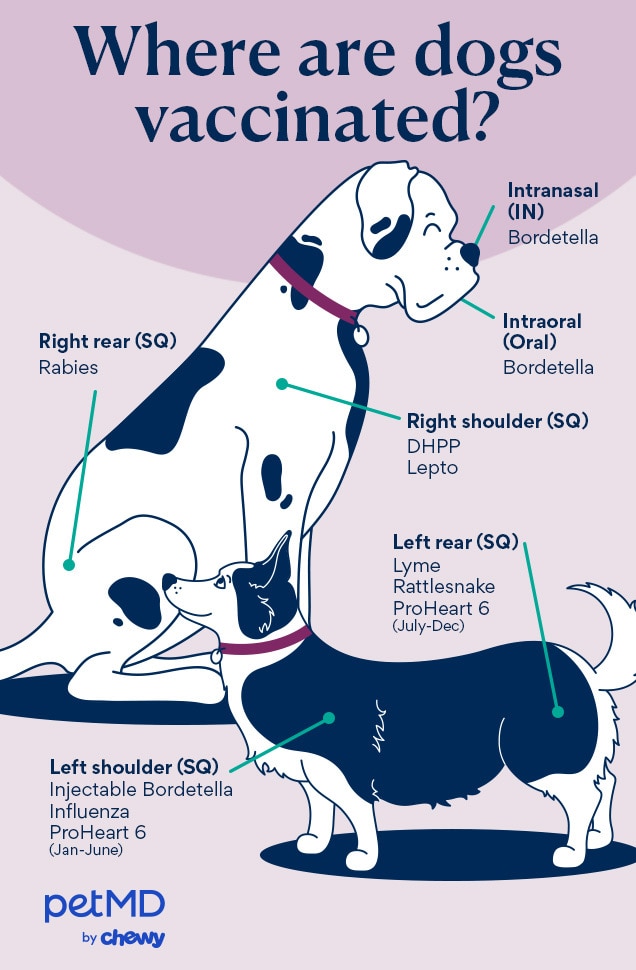

It’s common for dog vaccines to cause mild reactions, including discomfort or swelling at the injection site. Dogs may also develop a mild fever or have decreased energy and appetite for the day. But if any of these signs persist for longer than 24 hours, contact your veterinarian.

More serious side effects, such as anaphylaxis, can occur within minutes to hours of the vaccination. Seek veterinary care immediately if your pet shows any of the following symptoms:

-

Vomiting

-

Diarrhea

-

Swelling of the muzzle around the face and neck

-

Coughing

-

Difficulty breathing

-

Itchy skin

-

Hives

These reactions are much less common but can be life-threatening. Before your veterinarian administers any animal vaccines, alert them if your pet has had a reaction in the past.

Puppy and Dog Vaccines FAQs

How many vaccines does a dog need?

This depends on the age, lifestyle, and risk factors of a dog, and where the dog lives. Pet parents should talk with their veterinarian about creating an individualized vaccine schedule that meets their dog’s needs.

What happens if your dog is not vaccinated?

Unvaccinated dogs are susceptible to preventable diseases that can be expensive to treat and, in some cases, fatal. Some of these diseases, such as rabies and leptospirosis, can also be transmitted to humans.

Is it ever too late to vaccinate my dog?

No, it’s never too late to vaccinate a dog, even if they’re older.