Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs

What Is Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs?

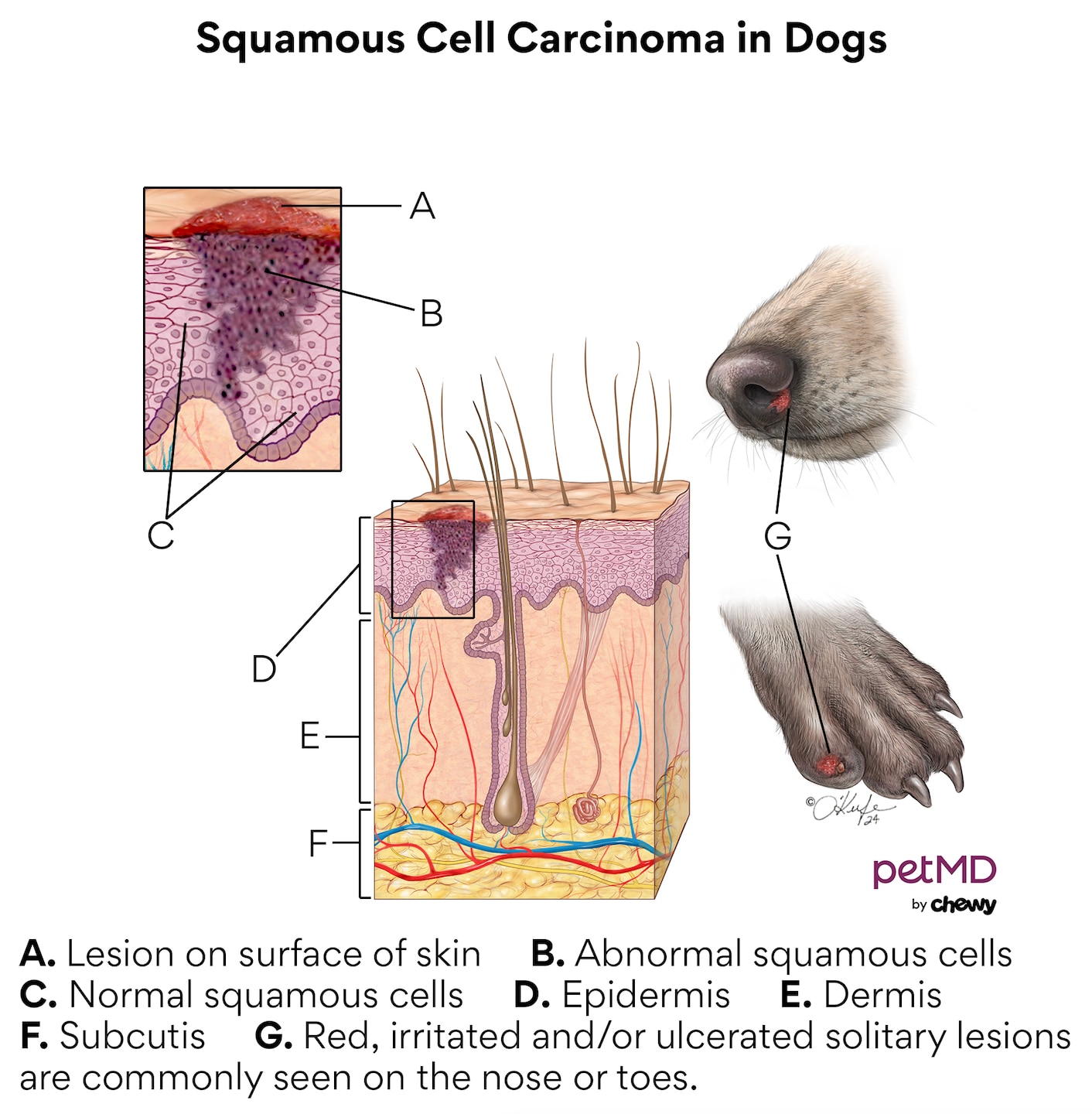

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the change, growth, and uncontrollable reproduction of squamous cells in dogs. These batches of unusual cells begin to form a malignant (cancerous) tumor. This is different from a benign, or non-cancerous, tumor.

Your dog’s skin is composed of three main layers. These layers include the subcutaneous layer (deepest layer of the skin, composed of fat and connective tissue), the dermis (second-deepest layer, containing tissue, blood vessels, and sweat glands), and the epidermis (surface of the skin).

The surface of the skin has three cell types:

-

Melanocytes—These cells are in the skin and eyes, and make pigment called melanin. They are found in the base layer of the skin.

-

Basal cells—These cells produce new skin cells and make up the middle layer of the skin.

-

Squamous cells—They are found in the outermost layer of the skin, toward the surface.

Squamous cell carcinoma can develop anywhere squamous cells are found in dogs, including:

-

The mouth

-

Paw pads

-

Nose

-

Abdomen

-

Ears

-

Nail beds

-

Back

-

Legs

-

Scrotum

-

Anus

It is typically categorized as oral (the mouth and nasal cavity), subungual (affecting nail beds and toes), or cutaneous (in the skin).

What Does Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) Look Like on a Dog?

Squamous cell carcinoma typically consists of a single lesion, or skin sore, somewhere on the body. The exception is multicentric squamous cell carcinoma, which produces multiple sores in more than one area. This is very rare in dogs.

Squamous cell carcinoma sores can differ from each other. They are often small, red, and irritated-looking in appearance. They can ulcerate break open or be covered by thickened patches of skin, called plaques.

Sores can have additional effects on a dog depending on their location and severity. For example, sores on the toe or nail bed may result in the loss of a dog’s nail. Sores that have broken open and exposed a dog’s body to outside germs may become infected, especially if a dog chews or licks the area.

Click here to download this medical illustration.

Symptoms of Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs

Symptoms of squamous cell carcinoma in dogs include:

-

Small sore(s) on the body that appear inflamed, red, covered in thickened skin, or bloody

-

Licking or chewing a certain area of the body

-

Missing toenails, blood on the floor, difference in walking or reluctance to walk

-

Excessive drooling with or without blood

-

Difficulty swallowing or chewing

-

Changes in walking, or the reluctance or inability to walk

-

Weight loss

Causes of Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs

Cancer is a complex disease. Your dog’s risk for getting squamous cell carcinoma depends on a few factors, including their genetics, environment, and family history.

Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light is a well-studied environmental risk. Another cause of squamous cell carcinoma could be canine papillomavirus ( papillomas or warts caused by viruses).

Squamous cell carcinoma is more common in certain breeds, such as:

Some breeds are likely more vulnerable because they lack hair or have light-colored fur or skin. It is unclear why some others are more susceptible. For example, a Rottweiler is more likely to develop squamous cell carcinoma on their toes, despite their toes being relatively dark.

Older dogs are more likely to be diagnosed with SCC than younger dogs. In a study of 17 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, the dogs ranged from 2 to 14 years old. Gender does not appear to be a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma. In the same study, there was a near equal split of males and females.

How Veterinarians Diagnose Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs

Your dog’s veterinarian will need to examine the squamous cells in the tumor to make a diagnosis. These cells can be taken by a fine needle aspiration (FNA) or biopsy (removal of a small piece of tissue).

FNA involves inserting a small needle into the tumor and taking a sample of cells. The sample is then looked at under a microscope. A biopsy is more involved, as it requires taking a piece of tissue from the tumor to be studied. Additional tests may be needed, depending on the results of these procedures.

Stages of Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs

Squamous cell carcinoma grows slowly but may spread to local lymph nodes or the lungs (metastasize) if not treated. However, cancer in toes may grow faster than other areas of the body.

Your veterinarian may perform tests to determine if the squamous cell carcinoma has spread to other parts of your dog’s body, particularly if it is present in the toes. This is called staging.

Tests completed for staging can include radiographs (X-rays), ultrasounds, and analysis of your dog’s blood, urine, and lymph nodes.

Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs

Surgery is the most recommended treatment option. The removal of a small skin lesion toward the surface of the skin that has not invaded nearby tissue can be a relatively routine surgery. Surgery that involves a large tumor or a tumor that has invaded nearby tissue is more invasive, and your veterinarian may need to replace lost skin tissue from another area of the body (skin grafting).

Squamous cell carcinoma on toes may be treated by amputation of the affected digit only. Amputation of the foot or leg may be recommended in extreme cases for advanced cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma in the jaw that invades the jawbone may result in removal of part of the upper or lower jawbone (surgical procedures called maxillectomy or mandibulectomy).

A mix of radiation and surgery may be suggested for your pup to ensure all diseased cells are destroyed. Like radiation, chemotherapy is also unlikely to be suggested on its own and should accompany your dog’s surgery. Not all dogs will be candidates for surgery. Some dogs may not be healthy enough to tolerate the anesthesia, or their tumors are inaccessible. Radiation, medication, and chemotherapy may be the only option in these situations. While they may not destroy all cancer cells, they can shrink tumors and prevent further growth.

If your dog’s tumor is caught early, your veterinarian may decide to remove it with cryosurgery. This involves freezing and destroying the cancer cells with extreme cold. Another option for the removal of early squamous cell carcinoma is photodynamic therapy. Photodynamic therapy uses drugs activated by light—known as a photosensitizer or photosensitizing agent—to destroy cancer cells.

Pain medication may also be given to keep your dog comfortable. Prescribed medications may include:

Your veterinarian will likely recommend an additional antibiotic to prevent any secondary infections.

Recovery and Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) in Dogs

Your dog will need to have regular check-ups after surgery to monitor the cancer for any signs that it is coming back.

Recurrence is rare, though dogs with multicentric squamous cell carcinoma may develop new sores after others have been removed.

You can help prevent squamous cell carcinoma by limiting your dog’s exposure to the sun. If you’re a pet parent to any of the vulnerable breeds, make sure to regularly check your pup’s skin, mouth, and toes. Consider using a dog-friendly sunscreen, especially in dogs with white or light fur/skin.

Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Dogs FAQs

How common are squamous cell carcinomas in dogs?

Squamous cell carcinoma makes up 5% of skin cancer cases in dogs. It is the second most common form of oral cancer in dogs.

Can dogs have moles?

Dogs can get moles anywhere on their body. Most are generally harmless, but some may be cancerous and will need testing by a veterinarian.

How long will a dog live with squamous cell carcinoma?

Depending on a dog’s tumor location and stage, survival rates with treatment range between 10% to 95% within the first year. Dogs with metastasized squamous cell carcinoma in or on their toes have the shortest life expectancies.

Featured Image: iStock.com/RossHelen

References

Chandrashekaraiah GB, Rao S, Munivenkatappa BS, Mathur KY. Canine squamous cell carcinoma: a review of 17 cases. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Pathology. 2011;4(2):79-86.

Luff J, Rowland P, Mader M, Orr C, Yuan H. Two Canine Papillomaviruses Associated With Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Two Related Basenji Dogs. Veterinary Pathology. 2016;53(6):1160-1163.

Lundgren B. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Dogs and Cats. Veterinary Partner. Published August 6, 2007. Revised November 30, 2022.

Marconato L, Murgia D, Finotello R, et al. Clinical Features and Outcome of 79 Dogs With Digital Squamous Cell Carcinoma Undergoing Treatment: A SIONCOV Observational Study. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2021;8:645982.